The following recommendations draw on the lessons from the yMIND project, and are offered as a guide to partners, school and community leaders, and policy makers seeking to embed and implement in new settings the yMIND good practice models.

Recommendation 1: Sell the wider education benefits of the good practice models

- The two good practices promoted by the yMIND project do not simply provide a framework to support the learning of children and young people (CYP) about diversity and address issues around discrimination, bullying and violence. In addition, through participation, CYP develop skills in communication and critical thinking. They are also required to reflect on and adjust behaviour. To this extent yMIND should be considered and described in terms of a whole school intervention, supporting other areas of the curriculum and school life.

- yMIND can be considered a whole-school strategy to identify social and personal problems individual CYP may be experiencing. Where schools have specialist support in place, such as educational psychologist, child protection officer etc, yMIND can be considered as an underlying programme to develop the broader context of empathy and tolerance for diversity that supports specialist interventions. It can also add to centres’ existing diagnostic processes for identifying CYP who need specialist support.

- Organised appropriately, yMIND can also provide home-school links and make the connections to the wider community which contribute to learner success.

- Use the case studies to illustrate the benefits of yMIND, and how it works in practice

Recommendation 2: Don't be afraid to address problamatic issues in the lives of the children

In practice, yMIND activities encouraged CYP to relate to problematic issues in their lives. When this occurs, professionals need to be prepared to deal with them.

- Use the case studies and information in section published in the website of this report to familiarise practitioners with the types of issues yMIND raises.

- Ensure practitioners conduct the preliminary focus groups designed for yMIND so that they have clarity on the sorts of issues they will be dealing with in their context. o Plan where the yMIND intervention will sit within the centre’s wider processes for dealing with pastoral education, special needs and child protection. Ensure there is clarity over referral pathways, for example, if a child discloses an incident of child abuse.

Be clear about what the centre’s, and the community it serves, starting point is in terms of: attitudes towards the themes of yMIND, and the interactive and CYP-led nature of the pedagogy, and tailor initial activities and conversations accordingly.

- Prepare the ground through conversations, focus group, and training activities with leaders and practitioners.

- Involve leaders and practitioners in yMIND activities from the beginning – avoid yMIND being an intervention conducted by outsiders, it needs to be integrated.

Recommendation 3: Promote ownership of the new practices by leaders and practitioners

To adopt new practice, leaders and practitioners need to ‘own’ it. A key mechanism for achieving this is co-construction – that is, practitioners are involved from the beginning in design, implementation, evaluation and revision of the new practice. Where co-construction is not possible, for example when using a resource and activity created elsewhere, providing choice is a helpful substitute, requiring practitioner to make decisions and therefore take responsibility for what they implement.

- When planning implementation of GP1 strategies and activities, allow practitioners to use the synopses to select which activities they will use, justifying decisions in the light of reflections on their own CYP

- Plan for feedback sessions or review workshops in which practitioners can adapt activities, or create new approaches based on yMIND principles, for themselves.

- Encourage practitioners to apply the principle of choice in their own practice, so that CYP too benefit from opportunities for decision making, and so increased motivation.

Encourage practitioners to use teaching logs to ensure reflection and to provide information for debriefing, and planning next stages.

Establish practitioners as pairs or buddies to review their application of the new practices, and encourage collaborative activities such as observation and feedback, and joint planning.

Ensure at least one senior leader is involved in professional development, either as participant or lead practitioner in training sessions, or through observation and feedback or modelling of the practice. Where there are mechanisms for performance review, encourage practitioners to discuss their implementation of yMIND, to help raise its profile on the management agenda.

Recommendation 4: Reinforce local and national messages on the benefits of interventions sharing yMIND principles

- Develop your network of organisations, professionals and community links that share the ethos of yMIND, and alert them to where and when yMIND is implemented

- Use the case studies and frameworks for effective practice to illustrate the benefits of yMIND and how it works

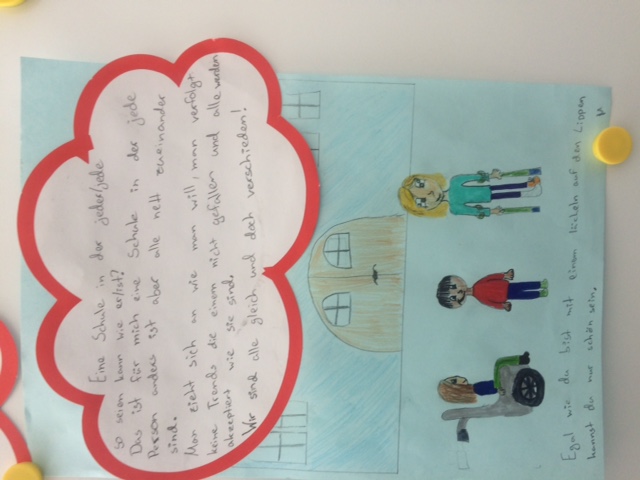

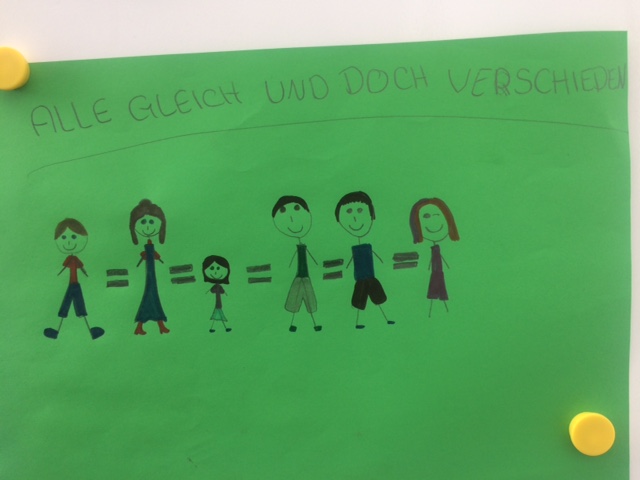

- Support centres implementing yMIND to develop their own case studies of its impact on individuals, and to display outputs

- Identify opportunities to link yMIND activity with regional, national and EU policies, and highlight these links with policy makers